Or how justified critiques can backfire

Carbon offset mechanisms are increasingly being criticized in the media[1]. Some of this criticism is justified and can contribute to greater rigour in the design, implementation and verification of these projects’ impacts. However, we must ensure that we do not end up with the opposite effect: making it impossible to invest in carbon projects that generate not only climate impact, but also wider environmental and social impacts, particularly projects implemented with the most vulnerable populations in developing countries. Bernard Giraud, Co-founder and President of Livelihoods Venture shares his concerns and calls for decision at COP28.

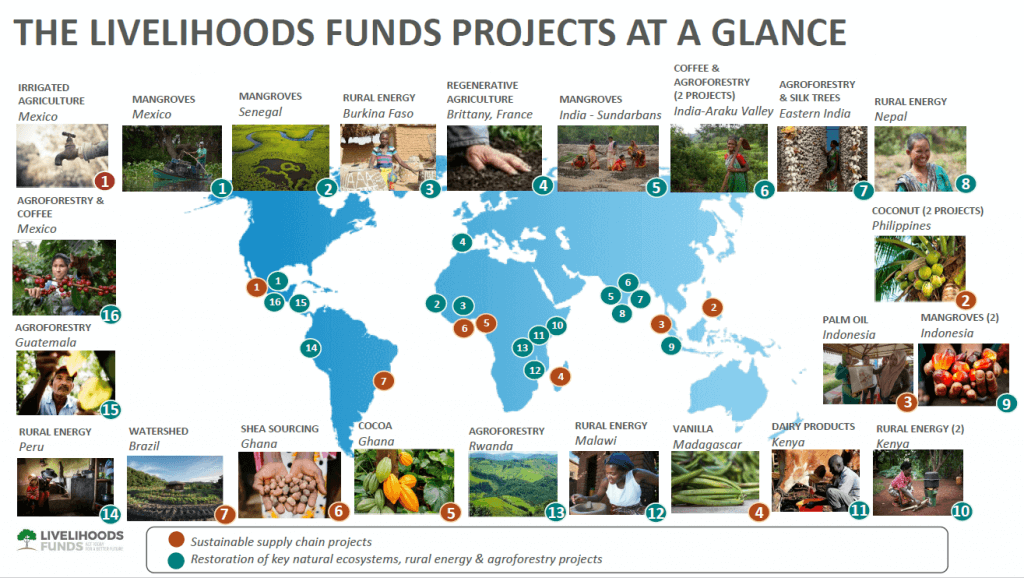

The Livelihoods Funds have been developed to meet a dual need: on the one hand, the need of companies that have set ambitious targets to reduce the carbon impact in their value chain but also to make a positive contribution to generating social and environmental impact by financing projects beyond their businesses’ scope. On the other hand, the need of supporting rural communities whose livelihoods depend heavily on natural ecosystems and resources.

Since the Livelihoods Funds were launched in 2011, the so-called “nature-based solutions” have enabled hundreds of thousands of farmers and their families to restore degraded ecosystems, learn productive and sustainable farming practices, regenerate soils and protect forests and water resources. In doing so, the funds have made it possible to store millions of tonnes of CO2 removed from the atmosphere or to reduce carbon emissions.

It’s not enough, but it’s not negligible either. IPCC experts (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and the negotiators of the UN Climate Conventions have continually emphasized the importance of protecting and regenerating the ‘carbon sinks’ that are ecosystems to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Not all carbon projects are equal

Are these projects perfect? Is carbon financing the solution to every problem? Certainly not. Several recent publications have pointed to highly questionable carbon projects. Some so-called avoided deforestation (REDD+) projects[2] have not led to the expected impacts. Some players in the carbon markets, motivated mainly by financial interests, have implemented practices that are open to criticism and, in several cases, are unacceptable. These criticisms are useful if they help to clean up and regulate a market that is still young and poorly structured. Recent initiatives such as The Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets (ICVCM)[3] can address the need to provide a much more robust framework for the production of carbon credits and the projects that generate them.

But we must be cautious. The widespread image conveyed by some external audiences is that all carbon offset projects are at best ‘greenwashing’ and at worst a way to extort money from vulnerable populations. This view is as false as asserting that all drivers are reckless or all taxpayers are fraudsters because a minority exhibit condemnable behavior. It is necessary to separate the wheat from the chaff, and not to condemn wholesale a financing model that can in fact be virtuous.

Not all carbon projects are the same in terms of aims, costs and impacts: financing the planting of single-species trees over thousands of hectares in a forest concession and helping several thousand small farmers to implement a diversified agroforestry model that will reduce erosion, restore soil organic matter and generate income are both “carbon sinks”. But their social and ecological impacts are completely different, as is the complexity of their implementation.

Carbon investments in high impact projects should be strongly encouraged

Livelihoods funds pre-finance large-scale projects over a twenty-year period. These projects are co-designed with local partners who are firmly rooted in local realities, most frequently NGOs, and implemented by these partners with local rural communities. None of these projects have the sole aim of producing carbon credits. They all aim to generate sustainable ecological and social impacts.

The companies that have invested in our funds are taking the risk of financing these projects in contexts that are often difficult, whether due to climatic or political reasons. These risks are real and have already materialized: they range from droughts, cyclones, to civil wars, etc. In return, investors in our funds receive carbon credits at their production cost. The Livelihoods carbon finance model as practiced with our investors is not financial speculation on hypothetical future carbon market prices. It is long-term investment by companies to create “green infrastructure” that helps improve the lives of communities who most often live off a very low income.

Instead of rejecting carbon financing out of hand, we should be encouraging companies to make greater commitments to support projects with high environmental and social value by creating a framework that facilitates and secures these investments.

Growing bureaucracy is complicating action on the ground

Obviously, we can and must improve the methods and techniques for measuring carbon that were introduced a few years ago. Scientific knowledge and new technologies have come a long way and must be mobilised to improve accuracy and reduce costs. In response to the criticism they have faced, carbon standards have embarked on revising their principles and the methodologies for measuring and certifying carbon credits. This revision is necessary, but it must take into account the realities on the ground and the specific features of projects implemented with the most vulnerable populations. Like other funds or organizations implementing nature-based solutions, we are facing a trend that concerns us: an increasingly bureaucratic approach with standards being set, often with little consultation, by multiple teams with little or no practical experience of the field realities of these projects.

The increasing complexity of the rules and procedures risks making it impossible to invest in projects involving thousands of small producers, which are already complex by their very nature. The difficulty these standards face in meeting deadlines for publishing new norms increases the uncertainty. Also, some practices are particularly unacceptable, such as changing the carbon methodology for projects that have been registered for several years under the same standards. It’s like changing the rules of football in the middle of a match.

Carbon standards should take into account the field realities

The effect of these trends and changes is not only to make projects more complex, but also to sharply increase costs and the “non-productive” part of budgets. By this we mean all the expenditure that goes to consultants, verifiers and auditors as well as registration costs, and not to small producers and local communities. The budgets devoted to measurement and certification efforts are already very substantial. It is important to maintain an acceptable ratio between the proportion of the investment that finances the project itself and the proportion that finances the measurement and certification activities.

It is equally important to set the requirements at the right level for each category of project. For example, the latest version of the Verra Standard requires stakeholders to be committed to project results for a period of 40 years. This requirement can be met in the case of large-scale industrial plantation projects in concessions. But how can the same commitment be demanded of small-scale farmers, whose 40-year commitment spans up to three generations? How to ask the grandchildren of the farmer with whom the project was launched to respect, under penalty of sanction, the commitments made by their grandparents in a world that was not the same?

At Livelihoods, we believe that the bulk of carbon financing should go to on-the-ground actions, and a balance must be struck so that certification processes and costs continue to fund projects that truly contribute to transformation. If this is not the case, we will collectively need to find other means of certifying our projects.

Urgent need for clear rules at country level

Another element of uncertainty for long-term private investors in carbon funds such as the Livelihoods Funds is the difficulty in obtaining clearer rules from governments regarding carbon rights. In application of the Paris Agreements, and in particular Article 6 (and 6.4) [4], each State is required to lay down the regulations applying to carbon projects: which projects are accepted in which activities and on which parts of the territory? Do they contribute to the country’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)[5]? What apply if carbon credits are transferred to other countries? Some countries have published their regulations, but in most of them, these rules have still not been published.

With this in mind, COP28 begins in Dubai, and we feel it is important for the monitoring body under Article 6.4 to propose concrete measures and guidelines to move forward on this issue. They have already met several times this year, but no legal framework has been adopted. As a result, high hopes have been placed on the review of policies during COP28, which could provide a platform for global carbon markets and facilitate understanding of emissions trading schemes.

Livelihoods’ call to COP28

At COP28, we believe it is important for various parties to come together to call on private and public players to take action and exchange information on the carbon market and also on sustainable policies. In addition, the conference will serve as a driving force for the adoption of concrete measures such as:

- Clearly assert the priority of nature-based carbon projects with a high environmental and social impact.

- create favourable conditions for investment in these projects;

- Recognise the specific nature of projects implemented with populations that are among the most vulnerable to climate change, and adapt the level of requirements for standards;

- Improve the measurement and certification processes, taking into account the complexity and constraints specific to these projects;

- Ensure a good balance between investment in the project itself and the costs of the measurement and certification processes.

In summary, carbon finance mechanisms can be useful contributors to sustainable development. They need improvement, but care must be taken not to hinder them with constraints that make investment in high-impact projects very difficult.

To date, the Livelihoods Funds have contributed to plant 148 million trees, to capture or reduce 4.3 MTCO2, restore or rehabilitate 38,000 hectares of natural ecosystems rich in biodiversity (such as mangroves or forests) and convert 50,800 hectares to sustainable agricultural practices. Overall, Livelihoods projects are contributing to improve the living conditions of 1.8 million people, worldwide.

[2] Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries. The ‘+’ stands for additional forest-related activities that protect the climate, namely sustainable management of forests and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks. Source: https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/redd/what-is-redd

[3] The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (Integrity Council) is an independent governance body for the voluntary carbon market. Learn more: https://icvcm.org/about-the-integrity-council/

[4] The article 6 is the Paris Agreement’s rulebook governing carbon markets, while the article 6.4 establishes a mechanism for trading GHG emission reductions between countries under the supervision of the Conference of Parties – the decision-making body of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

[5] Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of its long-term goals. NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. Source: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs