The water-soil-carbon nexus

Earth is referred to as the “Blue planet” or the “Water planet” as water covers more than 70% of its surface. Yet, 99% of our planet’s water is unusable by humans and other living things. Only about 0.3 percent of our fresh water is found in the surface water of lakes, rivers and swamps[1], most of our freshwater being in the ground. Since fresh water is mainly supplied to terrestrial landscapes by rainfall, the first element it finds on its way is the soil. Water accessibility and water quality are therefore dependent on healthy landscapes.

[1] https://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/earths-fresh-water/

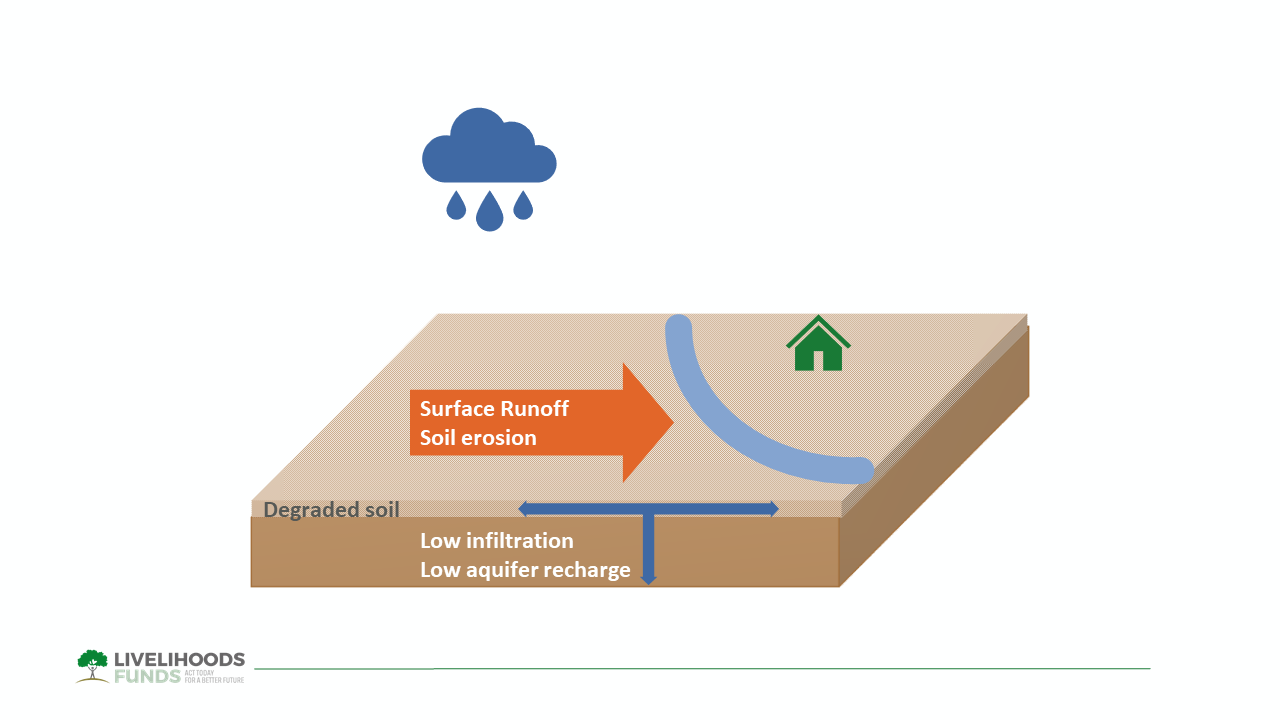

Degraded soil: increased runoff over infiltration.

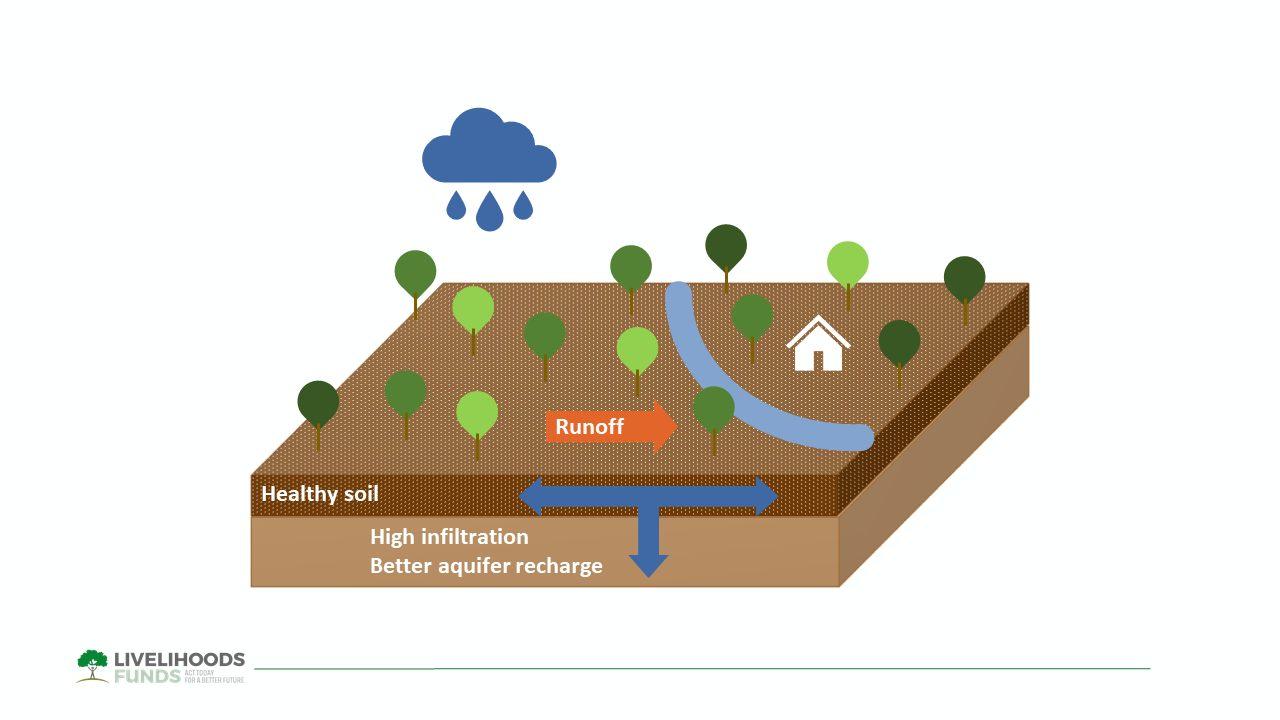

Healthy soil: a sponge increasing groundwater availability and reducing runoff/ soil erosion.

Soil varies a lot in composition, but to be healthy and support life, it needs to retain water and essential nutrients for plants, and consequently insects, worms, fungi, bacteria… Organic matter is a key component of a sound soil, as it acts as a magnet for water molecules and the nutrients attached to them. When soils are farmed, the practices applied may either preserve that organic matter, mostly concentrated in the top soil, or undermine it with runoff water, a phenomenon better known as erosion. An eroded soil progressively becomes mineral. It is less fertile and retains less water. Organic matter is in fact carbon. Enhancing the soil’s health therefore leads to a dual benefit as it can retain more water and sequester more carbon, thus mitigating water scarcity and climate change at the same time.

Simple, affordable and replicable farming practices such as composting, cover crops, agroforestry can increase the soil’s top layer resistance to erosion, accumulate a thicker layer of healthy soil and enrich it with organic matter. A healthy soil, sustained by these “Smart Agricultural and Land Management” practices (SALM), leads to multiple impacts on water availability and quality.

Groundwater availability

When rain falls on an agricultural plot under sustainable management, the uneven surface of the soil, covered with diverse plants and trees, makes it longer for the water to flow downstream through the plot. This leaves enough time for the water to penetrate the soil, thus limiting runoff. As the organic matter plays the role of a sponge, some water is captured in the thick top layer of the soil and made available to plants during a longer period. The rest of the water infiltrates deeper into the soil and recharges the aquifer. The soil’s organic content can be increased through very simple techniques sur as composting, mulching and no-tillage (leaving uprooted or sown crop parts to wither on a field)…The study conducted in the Livelihoods Mount Elgon project in Kenya with 30,000 family farms shows that by increasing the quantity of organic matter in the soil content by around 1 ton per ha each year though SALM practices, 17,000 liters more groundwater available per hectare. These farming practices can therefore have a deep impact on the food security of communities living in vulnerable geographies.

Water quality and biodiversity preservation

Since sustainable agriculture protects topsoil, the water that runs off outside of the plots is less likely to take away a part of the precious top-layer. For example, in Burkina Faso, farmers deploy stone rows following level lines, acting as mini-dams, to slow down surface run-off during heavy rains. In Kenya, farmers are planting trees along river banks to mitigate soil erosion and preserve rivers from sediments. Sedimentation leads to water pollution affecting the quality of water, aquatic life and the biodiversity of rivers, lakes, etc.

Climate action & crop productivity

The study in the Livelihoods- Mount Elgon project in Kenya also showed that with 1 extra ton of organic matter per ha per year, a healthier soil sequesters an additional 2,5 tons of C02 per hectare per year. Supporting farmers in the implementation of sustainable agricultural practices is therefore a key lever for climate action. What’s more, as it stores more carbon, the soil becomes more fertile leading to an increase in crop productivity and ultimately food security. By planting trees in their fields and by diversifying their crops to bring more biodiversity, farmers can improve the fertility of their soil and sequester more carbon.

Building on this soil- carbon- water nexus, the Livelihoods Funds’ projects aim at giving smallholder farmers in vulnerable communities the means and skills to give farmers the means and skills to act on water scarcity, climate change and food security though their agricultural practices. By bringing together private companies, public organizations, NGOs and the civil society, these projects can reach hundreds of thousands of people in Brazil, Mexico, Burkina Faso, Kenya…

Photo: Jurga Jo/ Adobe Stock.