LIVELIHOODS LAUNCHES AN UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE IN GHANA TO HELP LIFT FARMERS OUT OF POVERTY

Cocoa, the main ingredient of chocolate, is enjoyed by consumers all over the world. The global demand for cocoa beans has skyrocketed since the 1990s, reaching 5.6 million tons of world production in 2019 [1]. Grown on land located around the equator, the fruit is produced by close to 6 million smallholders, whose livelihoods depend on it. Yet paradoxically, most cocoa farmers are stuck in a poverty trap, especially in West Africa which accounts for over 70% of the global harvest.

Ageing trees, lack of access to quality technical skills and sustainable financial means to regenerate the soil and boost productivity, are among the key reasons. In Ghana, the second largest cocoa producer, the private and the public sector have made significant efforts in the past few decades to source cocoa sustainably. But these initiatives have shown limited improvement on cocoa smallholders’ income, particularly in the context of earning a living income. Which practical solutions could help farmers sustain their families’ needs out of cocoa? Can farmers couple land restoration with increased income?

After shea, Livelihoods is launching a new initiative in Ghana (check out our sustainable shea sourcing project) to uncover and address the social, economic and environmental problems faced by cocoa smallholders. The project has one specific goal: identify which levers can help cocoa smallholder farmers sustainably restore their farms and improve their income. This 3-year initiative is launched by the Livelihoods Fund for Family Farming (L3F) which has brought together: Mars Incorporated (global business that produces some of the world’s most famous brands of confectionery, food, and pet care products), Touton (a decade-long major player in global cocoa trade and Mars’ main cocoa supplier), Solidaridad West Africa (a civil society organization with extensive experience working with cocoa smallholder farmers in West Africa) and Institute for Development Impact (I4DI) (entrusted monitoring, evaluation, and learning partner to evaluate the project’s impacts).

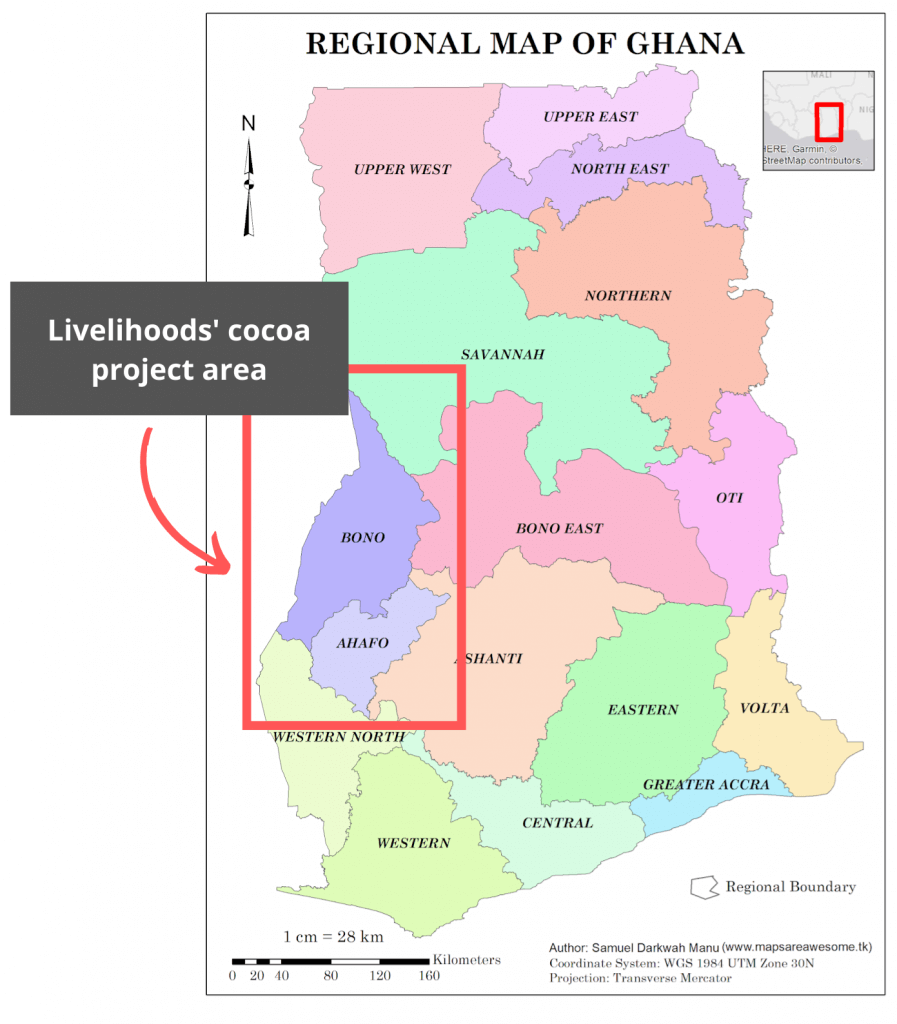

The project is implemented in three cocoa districts namely Nkrankwanta, Kasapin and Sunyani located in the Bono and Ahafo regions of Ghana. The overarching goal of the project is to find a sustainable sourcing model that will accelerate farmers’ transition to a decent living income [2] in a test & learn approach, with the possibility of replicating the good results in the Ghanaian cocoa sector after the current phase.

In Ghana, cocoa is the main source of income to independent smallholder farmers

In Ghana, the world’s second largest producer after Ivory Coast, cocoa is the main source of income to 800,000 cocoa farm families in the country. But the challenges they face at farm level are many, and the income they get from cocoa harvest is not high enough for a vast majority of them to meet their families’ basic needs such as: food, clothing, decent shelter, healthcare, and education. This deprives them of the income needed to invest in sustainable production on their cocoa farms.

Indeed, in the regions of Bono and Ahafo where Livelihoods’ project is being implemented, close to 80% out of the 1,000 farmers identified for the project, do not reach a decent living income that would help them meet their basic needs and to invest in their cocoa farms. In other words, smallholder cocoa farmers are caught in a poverty trap despite decades-long efforts made by key stakeholders (private and public) of the cocoa sector to transition smallholder farmers out of poverty in a sustainable and responsible manner.

Poor soils after decades of monocropping

In Ghana, farmers grow cocoa trees on farms of 1 to 4 hectares on average, which they have inherited from their families. Beyond cocoa, smallholder families usually grow staple food crops like maize, plantain, and cassava, but cocoa remains the major economic activity to feed families of 5 members on average (the parents and 3 siblings & or children). With cocoa farmers being 55 years of age on average, the sector needs to take up the challenge of designing attractive conditions for the new generation of farmers who will inherit the cocoa farms.

(Photo Credit: I4DI)

The first major challenge independent smallholders face is soil fertility, which has declined in the past years because of permanent land use that leaves no time for the soil to regenerate. Decades of deforestation and cocoa monocropping to answer a fast-growing global demand, without compensation of soil nutrition, have affected soil health. In time, cocoa trees have been taken out of their natural conditions and ecosystem (cocoa is a shade-loving crop): today, the lack of adequate shade trees on cocoa farms makes way for direct sunshine which contributes to soil infertility. The over-use of herbicides and the effects of climate change have further aggravated soil fertility.

Lack of labour force at the farm level

At the farm level, cocoa smallholders are also confronted to a lack of skilled labour force which affects their production capacity. A husband and wife can efficiently look after a cocoa farm of 2 hectares, but anything beyond that will require additional skilled labour which they usually cannot find nor afford. Today, cocoa farms’ productivity has stagnated at less than half their potential: the average cocoa yield in Ghana is currently 450 kilograms per hectare, whereas a well-managed cocoa farm could produce between 1 and 1.5 tons per hectare [3]. Cocoa is a labour-intensive crop during the harvest and post-harvest activities (mainly from September to February), and for the plots’ maintenance (January to July) in which farmers are directly involved. It is one of the few crops in Ghana that is still grown and harvested purely by hand.

Farmers must protect their cocoa trees from wind and sun. Pruning, which is essential to increase yields and reduce pests & diseases pressure, is an arduous and technical practice. Smallholders also need to invest time to eliminate weeds, fertilize the soil and prevent the cocoa beans from pests and diseases. During harvest season, cocoa pods are hacked open using machetes to extract the beans, before they are allowed to ferment, dried, bagged, weighed and sold to licenced buying companies through their purchasing clerks.

In the project area, 30% of cocoa trees are above 35 years old: replantation of the oldest plots is critical for traditional farms whose productivity cannot be restored with sustainable agricultural practices alone. An increasing quantity of trees could further be affected by diseases, in particular a virus called “CSSV” (Cocoa Swollen-Shoot Virus) which primarily infects cocoa trees and decreases yields within the first year of infection. The virus, transmitted from tree to tree by mealybugs, can spread even more rapidly in a monocropped farm and usually kills the trees within a few years. More sustainable agroforestry models, relying on diversified plots, but also with healthier soils rich in micro-organisms could help the trees resist better pests and diseases.

The cocoa paradox: why are smallholders stuck in a poverty trap?

Farmers are stuck in a vicious circle where, on the one hand, unsustainable production models based on monocropping focusing on productivity only have led to depleting soil fertility. On the other hand, farmers lack the technical skills, financial means, access to labor, or basic infrastructure to move to sustainable diversified models where they would earn more out of the land they cultivate. In this context, it remains complex for them to make the decision to invest in the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and/or the necessary replanting activities on their plots.

In the past few decades, the cocoa sector has defined techniques known as “Good Agricultural Practices” that aim to maximize farm productivity and resilience. These practices, (as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization – FAO) answer to a set of principles which aim to ensure a safe, sustainable production of crops (and livestock), while maximizing yields potential. Good Agricultural Practices are thought to minimize production costs for the farmer and the environmental impact of farming activities. Applying these practices on farm reinforce responsible farming models which result in safe, healthy soils and quality crops. With the overall intention of respecting the crops’ natural cycle and surrounding environment, GAP includes techniques such as tree pruning, soil fertilization, treating and managing potential diseases and ensuring soil health by supporting living organisms in the soil. In addition, restoring degraded land, preserving surrounding natural resources, minimizing waste, using water sustainably are areas of further action. Once adopted on-farm, these practices can ensure healthy fertile soils, which in turn can also double productivity. Learn more about the principles and examples of Good Agricultural Practices.

Yet it seems that over the last two decades, many farmers were trained on the above-mentioned practices, but the observation in the field is that only 30% of farmers currently adopt them. Adopting the Good Agricultural Practices on their plots requires intensive labor and financial investment over time, which often requires bank loans, which aren’t accessible to many smallholders, especially female farmers. Plus, with current interest rates which are as high as 50%, low harvests due to diseases, and declining weather conditions might leave farmers with debts they cannot repay. So, they don’t take the risk. Plus, long-term loans for replanting are not available to them.

“Several programs have asked me in the past to plan and manage my farm better. I know what I need to do but I cannot afford the quality inputs and labor force to make it happen. It is too risky for me now to borrow money and prices keep increasing!”

Overall, farmers would need to, at least, triple their production costs to apply these practices compared to their current low base. This involves hiring additional labor, purchasing inputs and equipment, accessing quality fertilizers and organizing their transportation. But to date, the access to quality seedlings and fertilizers remains complex. Seedlings are not always available, transportation costs are high, access to labor is disorganized and expensive. What is more, when smallholders invest into replanting activities, they must get through the first 3 to 4 years with even lower income, before the newly planted trees start producing cocoa beans in commercial quantities.

In a general context where the cocoa price is fixed by the Government yearly and productivity is declining, most farmers’ income remains low discouraging the next generation The buying price for cocoa in Ghana is defined yearly by the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) which controls all exports and protects the farmers from volatile prices. In 2021, the price for 1 kilogram of cocoa beans was fixed at an equivalent of 1 dollar. In the project area, the average annual income from cocoa production is around 1,275 dollars equivalent, which is far below the decent living income calculated at around 2,200 dollars per year, making smallholders unable to invest in the development of their farms.

“It is difficult for a young woman to generate sufficient income and become financially independent in the couple as they do not often have access to the land. And when they have, and especially for female headed households the challenges we face is to find workers in the neighborhood that are qualified and know how to restore soils and take care of new plantings”.

How can the private sector contribute to improving farmer income? Should it pay bonuses for the adoption of good agricultural practices? Should it help improve farm productivity to address quality and increasing market demand? How can the private sector aid farmers to couple productivity and sustainability by shifting to a model where farms become more resilient?

Is there a way out of this vicious circle?

Livelihoods and its partners are raising these crucial questions: which sustainable model can contribute to lift cocoa farmers out of poverty? And how can we help the transition to more sustainable agroforestry models where farmers can earn more from a thriving land? Livelihoods, Mars, Touton, Solidaridad West Africa and I4DI are launching an unprecedented 3-year initiative to identify which levers could help achieve this transition to a more resilient, prosperous cocoa farming in Ghana. The project is addressing the overall farmers’ needs (including farming skills, financial means, and external labor) to boost the adoption of Good Agricultural Practices and invest in the necessary replanting activities. This is an agile approach that will allow the coalition of partners to test out different parameters in independent clusters of farmers and adapt or tweak them if necessary. Their common goal is to help farmers gradually reach a decent living income.

The test and learn approach will help answer some key questions such as:

To what extent does intensive coaching affect Good Agricultural Practices adoption rates?

One thousand independent farmers within Mars-Touton supply chain will participate in this initiative and will benefit from a package of interventions to achieve this transition. They will benefit from technical training and individual coaching to boost the adoption of enhanced agricultural practices which will help restore degraded soils (pruning, techniques to put carbon back in the soil, adapted fertilizers etc.). The project will provide intensive on-farm coaching to support farmers with long-term adoption of agricultural practices adapted to their plots. With healthier, fertile soils, farmers could double their productivity and ultimately their income.

Are farmers willing to pay for farming services (labor, inputs)? Is there an attractive model to set up more Service Providers?

All farmers will benefit from the organization of reinforced cocoa farmer groups that will help them assess their needs, be it training, farming inputs, financial mechanisms, but also reinforce peer-to-peer learning. The project will assess these farmer needs, and in the long run, potentially facilitate access to government programs that will support them with technical skills, farm regeneration etc. The project will also test whether farmers benefit from facilitated access to service providers who will deliver specific services to them (inputs and labour) to support the management of their farms.

Which short-term financing solutions would boost the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices? Would long-term loans make a difference in engaging replanting activities? Which type of compensation would boost replanting?

The project will facilitateaccess to affordable short-term loans for participating cocoa farmers at an annual interest rates of 24% and 12% instead of the current 50% on the market. This is to ensure that the farmers have adequate financial resources to invest in sustainable cocoa production. Where replanting is needed, smallholder cocoa farmers will benefit from access to long-term loans (which today are not available to them) at an annual interest rate of 12% on the local currency. Farmers who will invest in replanting will also benefit from financial compensation to help them get through the initial 4 to 5 years when the newly planted trees don’t produce beans in commercial quantities.

The initiative will roll out a methodology in which different variables will be tested into small clusters of farmers (groups of 100 farmers). The results will be measured regarding the adoption of agricultural practices and replanting, before being replicated into a bigger group within project farmers if proven fruitful. Short and frequent feedback from the farmers will be gathered by field coaches to adjust efforts accordingly.

A special attention to women in cocoa

The project will adapt interventions to enable women, who make up 30% of the project farmers (a number that is higher than the national average), to participate fully and benefit from all the activities. The analysis of results will be also performed in a gender sensitive way to identify specific obstacles for women, and structure solutions for them, especially as they manage their households’ needs.

At the end of the project, the goal is to come up with the most efficient selection of interventions that have indeed helped farmers improve their income. This unprecedented Test and Learn project, will help clarify realistic pathways towards decent farming income for farmers, and eventually farms that are resilient, diversified, profitable, and that do not contribute to deforestation or unsustainable crop production practices. If proven effective, this blueprint would be rolled out to cocoa supply chains across West Africa in collaboration with a coalition of key cocoa suppliers (private sector, non-governmental organizations, financial institutions…)

[1] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – a specialized agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger.

[2] 332 dollars per month for a family of five people in 2018

[3] Source: Farmgrow, 2020: https://www.farmgrow.org/. Living Income is the net annual income required for a household in a particular place to afford a decent standard of living for all members of that household.