LIVELIHOODS LAUNCHES AN UNPRECEDENTED PALM OIL SOURCING PROJECT IN INDONESIA TO BUILD A SUSTAINABLE SUPPLY CHAIN WITH 2,500 SMALLHOLDERS

In a context where palm oil is both massively used by global industries and equally controversial, is there a way forward to build a more sustainable and inclusive supply chain? Can reducing deforestation meet with improved livelihoods for smallholders? How to drive the transition to sustainable sourcing with them?

For decades, millions of smallholder farmers in emerging economies have relied on palm oil to make a living. And today, the challenges they need to face are many: from competition with large plantations to declining productivity or lack of financial means to regenerate their ageing trees, smallholders are still mainly left aside of the transition to sustainability.

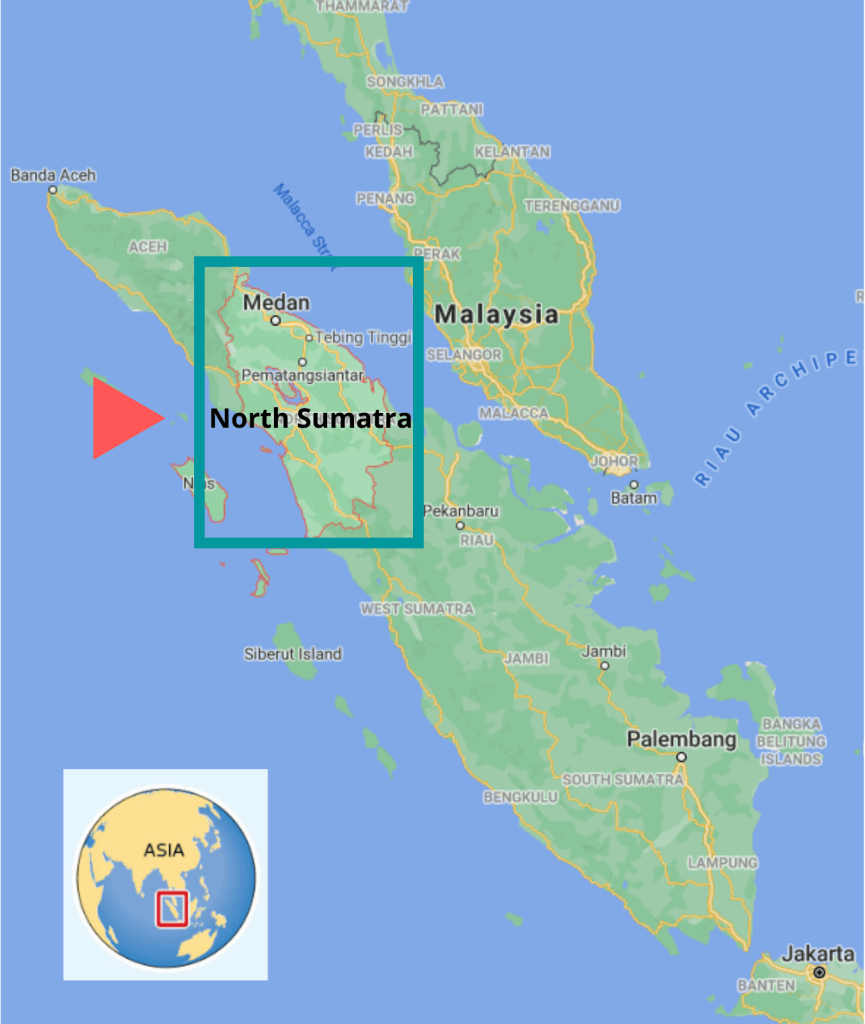

Faithful to its approach of learning by doing, the Livelihoods Fund for Family Farming (L3F) is launching an unprecedented 10-year project to help 2,500 smallholder palm oil farmers achieve this transition in Sumatra island, Indonesia. The project aims to build a transparent and deforestation-free supply chain thanks to locally adapted agroforestry models, regenerative agriculture and biodiversity enhancement. Brought together with Mars Incorporated and Danone, (both lead food brands, historic partners, and investors in L3F), L’Oréal (leading beauty & cosmetics brand) and implemented locally by Musim Mas (lead processor of palm oil) and SNV (entrusted project implementer working closely with palm oil smallholder) the project will help regenerate 8,000 hectares of palm farms in degrading land areas, while restoring additional 3,500 hectares of local biodiversity over 10 years.

In North Sumatra, smallholders have been producing palm oil for the past 30 years

Palm oil is an edible vegetable oil that comes from the fruit of oil palm. As they naturally need high rainfall, sunlight, and humid conditions to grow, palm trees are mostly present in the tropics, across West and Central Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia. Today, Indonesia and Malaysia provide on their own over 84% of the global production.

Sumatra island, Indonesia, is a familiar territory to Livelihoods. Both Livelihoods-mangrove restoration projects implemented with local NGO Yagasu, contribute to restoring the mangrove ecosystem along the coasts of Aceh & North Sumatra, while boosting economic opportunities for rural communities.

This time, Livelihoods is launching a palm oil supply chain project in the province of North Sumatra, to help structure a sustainable transition with 2,500 smallholder farmers who are independent from palm companies. The project will take place in the supply shed of Musim Mas, and in districts located up to 50 kilometers away from its mill “PT. Siringo Ringo”. With a history rooted in Indonesia, Musim Mas is an industry leader operating in the palm oil value chain from plantations to mills and to refineries. As such, Musim Mas is a key supplier to Mars, Danone and L’Oreal, working closely with international traders and processors who are Tier 1 suppliers and provide these brands with the components they need. Musim Mas works closely with smallholder farmers who represent about 40% of its supply shed.

At farm level, palm oil is often a monocrop and a central source of income

Most independent smallholders in the project area produce palm oil as a monocrop and rely on it for their livelihood. 80% of them own small-land size plots of 1 to 2 hectares while 20% of them own medium-size plots, from 2 to 4 hectares. But the income they get from palm is not always enough to make ends meet. Without any other sources of income, owners of small-size plots often need to work in neighboring farms to provide for their families’ needs.

Farmers mostly rely on household labor. Palm oil management is an activity mostly led by men, but women traditionally play a complementary role to support their husbands. Their on-farm activities include picking up the loose fruits fallen from the palms, weeding, or applying fertilizers. But between the agricultural work and their household responsibilities, this leaves no additional time for them to engage in complementary economic activities that could support family income.

Mr. Panapang cultivates 3 hectares of palm oil and 4 hectares of rubber. His palm trees were planted by his parents over 30 years ago. He is looking for the right opportunity to plant new trees and boost his plots fertility.

From the farm to the mills, where quantity often prevails quality

Smallholders collect the fruit bunches from their palm every two weeks, all-year round, to reach an average productivity of one ton per hectare and per month. There is a limited number of active smallholder organizations in the area, therefore smallholders entirely rely on local agents located in their villages, to sell their production. Farmers sell their fruit, known in the industry as Fresh Fruit Bunches, to the agents and get paid immediately (or on the same day) in cash. Palm fruit bunches need to be transported to the mill in the 24 hours following harvesting.

In turn, agents transport and sell the fruit bunches to the mills (either Musim Mas’ own mill or others) that will later process it to produce crude palm oil (the edible oil extracted by the red pulp of palm fruits and later used in the food industry) but also palm kernel oil (extracted from the white kernel, and later used mainly in the cosmetics industry). Agents operate independently and determine the price. But this price smallholders get from agents is flat: it doesn’t fluctuate whether the production is of good or bad quality. In the current model, smallholders don’t access the mills directly.

Most farmers are organized into Farmer Groups. Mostly established to help them apply for subsidized fertilizers from the government, Farmer Groups have limited organization, management, and business capacity. As they are not perceived as bankable, they lack financial capital to support their members in purchasing fertilizers or other inputs needed.

Ageing palm plots keep farmers at risk and put pressure on forests

Smallholders represent 40% of the total oil palm area and an estimated 35% of the total crude palm oil production in the country. Yet they are still quite neglected in the industry’s transition.

The first challenge they face is at plot level: ageing trees planted in the 80s and 90s now produce less, yields are decreasing, thus directly weakening their income. With palm oil accounting for 60% of their income in average, smallholders currently earn just enough to cover their families’ basic needs. A recent field study showed that ageing palms might reduce productivity by 40% in the next ten years if no replanting is undertaken. This might lead to farmers searching for new areas to convert to palm plots, thus threatening the surrounding forests.

Thirty years of monocropping have also led to land degradation and reduced soil fertility (no diversification of nutrients and micro-organisms in the soil has affected soil health), which in turn reduces productivity and fruit quality. As they don’t have alternative sources of income with similar market demand, farmers are confronted with price volatility risks in a highly competitive market.

Field studies revealed there is a great opportunity to increase palm productivity and ecosystems services, thus reducing threats to surrounding forests, by replanting with improved oil palm varieties and improved agricultural practices.

Livelihoods bets on agroforestry and regenerative agriculture

The project will implement an innovative 360° approach to help farmers regenerate their ageing plantations, restore, and protect surrounding forests. But also move to an economic model that will help them earn more from their current plantations, and from new sources of income.

To achieve this, Livelihoods and its partners will leverage existing dynamics, located at both supplier and government levels. The project will amplify Musim Mas initiatives with smallholders: it has been engaged since 2015 in the largest palm oil independent smallholders’ project in Indonesia. To date, more than 43,000 farmers have been trained to sustainable land practices thanks to this initiative and 750 independent smallholders have achieved RSPO certification [1]. The project aims to reach a wider scale, by accompanying 2,500 smallholders during 10 years.

Boost farms productivity thanks to regenerative agriculture:

At plot level, the project will help farmers adopt regenerative agricultural practices that will restore soil health, increase fertility, to ensure better yields and fruit quality. These practices include introducing organic fertilization through composting, cover cropping (introducing nitrogen fixing plants to restore soil health and balance) and mulching. But also practices that integrate pheromone traps to control palm insect pest. For instance, integrating owl’s nests on the farm plots will help reduce rodents and protect the fruit.

Farmers will benefit from training sessions to acquire technical background and skills to transition to regenerative agriculture. In close partnership with existing farmer groups, village administrations and coordinated by local implementer SNV, demonstration plots will be developed to boost dissemination but also train farmers who in turn will support their peers. All farmers will also be equipped with a starter package that will include cover crops seeds, attractive plants seeds, pheromone trap for pests, nests for predators (barn owl) and breeding units for pollinators (weevil beaver). This equipment will help them reduce the use of pesticides while naturally boosting soil fertility.

Soil health is a crucial element of regenerative agriculture. One of the project’s innovative solutions will be setting up dedicated organic composting units located both at farm and farmers’ group levels. The composting will be based on animal manure and palm plot biomass residues – mainly solid Empty Fruit Bunche and liquid Palm oil Mill Effluent), to help farmers access organic fertilizers more easily.

Help finance the replantation of ageing palms:

50% of the palms in the project area are projected to become senile within 10 years. Replanting new palm plots is a major concern to boost productivity, especially for farmers who own 1 to 2 hectares of land and cannot afford to finance this replantation. The project will put in place a dedicated financial scheme to help them finance the replanting.

This will take form in implementing a financial facility with local institutions, local banks, loan facilities and credit risk assessments. It will leverage a successful 2-year initiative by Musim Mas, who implemented a pilot with 52 farmers.

Create new sources of income by integrating new crops:

With a density of only 144 palms per hectare, palm plots leave most of the soil uncovered during the new palms’ growth period: 3 to 4 years. Intercropping with annual or semi-perennial food and cash crops is an excellent opportunity for smallholders to generate additional on-farm income. Identified crops include those for which there is a strong local market demand: vegetables and fruits like watermelon, shallot, tomato, or chili to name a few. Many of them can be grown within newly replanted palm trees without competing for nutrients, water, or sunlight.

By covering the soil and leaving biomass after harvest, these vegetables will help control erosion, maintain humidity, and recycle nutrients, positively impacting soil health for more productive palm. To move forward in the regenerative agriculture transition, long-term intercropping alternatives will also be tested with motivated farmers to boost the integration of both perennial trees (fruit, nut, and timber) and animals (poultry, goats but also cattle).

Watermelon (left) & pepper (right) to be used in an intercropping model as a diversified source of income during the 3 to 4 first years of newly planted palms.

Create an economic and social infrastructure that valorizes smallholders in the value chain

Livelihoods’ project in North Sumatra is putting smallholders at the heart of an economic model that will help them increase productivity, restore soil fertility, sell better quality fruit. But the approach is also highly social. The project will rely on existing farmer groups to facilitate dissemination of good practices and boost mutual support. For instance, the project will promote seed investment facilities at village level, that will help farmers diversify their source of income in their farm, according to their needs and wishes. These facilities will for example promote the setup of vegetables gardens, poultry raising and goat breeding to support farmers’ income. They will particularly target women and the youth, to help them reach higher responsibilities in farm activities.

At market level, the project will facilitate the set-up of cooperatives, that will play a key role to structure stronger farmer organizations with a real positioning in the value chain and access Musim Mas mill more directly.

Restoring additional 3,500 hectares of local biodiversity in surrounding forests

In total, 8,000 hectares of productive palm will be covered. The project intends to go one step further and promote agroforestry models in surroundings forest areas, in which growing oil palms is not allowed. These models, based on non-palm agroforestry will be designed first to adapt to riparian areas (currently under palm production) but with the adequate replanting activities and second, to highly degraded ex-logging areas inside the forests together with the local government.

Intervention in these sensitive areas will serve as a buffer between palm production areas and standing protected forests. This implies working with existing Forest Farm Groups and the Forest Management Unit (FMU) to restore and preserve forestland starting with 500 hectares. The long-term project goal is to scale-up to 3,500 hectares of protected forest area, rich in biodiversity (with the support of public partners and a specific grant).

- [1] More about the Roundtable of Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)